Warning: The following article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice. The author is not a registered financial advisor and does not provide investment recommendations. Any investment decisions you make should be based on your own research and analysis.

Additionally, please be aware that the author may have a financial interest in the securities discussed in this article. The author reserves the right to buy or sell any security mentioned in this article at any time, without prior notice. Therefore, the information presented in this article should not be considered as a solicitation to buy or sell any security. Please consult with a registered financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Company name: Card Factory plc

Ticker: LON:CARD

Price: £1.06

Market Cap £359m

Introduction

Since my last post on Card Factory plc, the greetings card specialist from the UK and the country's number 1 value-for-money retailer, not much has happened that warrants this update. However, with the slow summer months, I feel like writing something, and with the stock being flat since my write-up on April 21(I recommend reading that write-up first), I feel the stock is as cheap ever. And poses a great opportunity to talk about Total Enterprise Value (TEV) and magic formula stocks terms popularized by Joel Greenblatt.

My previous write-up on Card Factory:

Card Factory a small giant

Company name: Card Factory plc Ticker: LON:CARDThanks for reading Iggy’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. Price: £1.02 Market Cap £350m Warning: The following article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice. The author is not a registered financial advisor a…

The Price Story

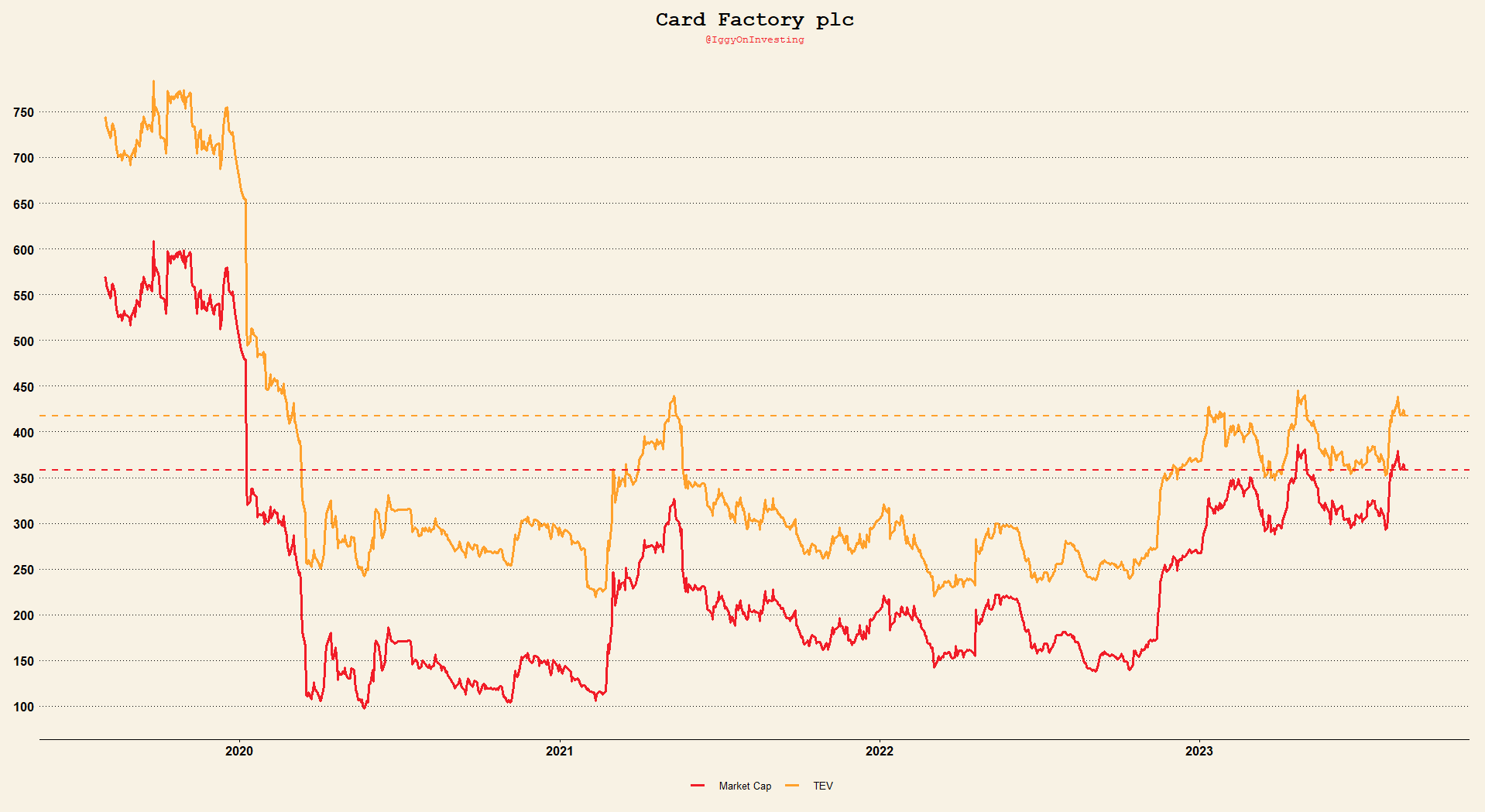

Although I find it hard to prove the exact "intrinsic value" a private buyer would pay for a business, sometimes it is quite easy to demonstrate that a stock is undervalued. I believe this is the case with Card Factory, and I will show this by discussing the price action in the stock from just before the COVID-19 pandemic until the current time. Let's start by looking at the development of the Market Cap from 2019-07-31 until last week's Thursday, 2023-08-24:

One might draw a quick conclusion with a brief glance at this chart, that the drop from close to £600m in Market Cap all the way down to Covid lows of £100m is all due to the lockdowns and the extremely destructive consequences for brick and mortar retailers like Card Factory. The initial drop at the end of 2019/start of 2020 is likely due to investor dissatisfaction with the business performance and CEO Karen Hubbard.

To quote from Cockney Rebel exellentsubstack post “Card Factory - an undiscoverd Zulu?”:

Card Factory floated 9 years ago in June 2014. It doubled in price from £2 to £4 in just over 15 months. Karen Hubbard succeeded Richard Hayes as CEO in Jan 2016 - a disaster. The company under-performed and over 4 years of investor value-destruction the shares dropped to 97p at the end of 2019. A month later Covid erupts, and by March, Card Factory hit 36p from its 400p high a few years before. Karen Hubbard resigned and by the July 2020 interims the co had net debt of £144m ex leases and sales of just £110m in H1, losing 5.2p a share in H1 and a market cap of circa £100m. Card Factory looked like a terminal decline hastened by Covid, they looked sure to need some form of very dilutive funding like so many businesses during COVID with even more debt to mkt cap, and lockdown wasn't over - and no CEO! - Peak gloom! ~ Cockney Rebel

So July 2020 was the peak of desperation for Card Factory – no CEO and a horrible capital structure to weather the lockdown. Card Factory was basically run like a public LBO (leveraged buyout); the stock had £145m of debt going into the pandemic with the last full year of earnings being £50m, resulting in a 3 times debt to earnings ratio. Adding to that, Card Factory leases all its stores, making the stock appear like a prime Covid casualty. For most of 2020, Card Factory equity traded below the value of the debt.

On March 8th, 2021, Card Factory finally got its new CEO, Darcy Willson-Rymer, who had previously successfully led Costcutter for 9 years. After a short rally, the stock started a path of decline again when the company announced on May 21, 2021, that it had agreed to a refinancing deal with its banking syndicate. However, although this deal gave them some short-term cash to survive, it had terms that forced the company to raise £70m in equity or subordinate debt. Equity holders were looking at the possibility of huge dilution, and there was no clarity from the UK government on when stores could finally open.

Although Darcy, as the new CEO, did not have a major shareholding yet, he and his team did everything to pull cash out of the company to pay down the debt in time, thus preventing dilution. Despite facing the challenges of physical stores only being open in 2021, they managed to generate enough cash to avoid dilution and pay off £20m in delayed rental expenses. This achievement led the banking syndicate to waive the obligation to raise £70m in equity on April 21, 2022. I believe this speaks very well of Darcy's commitment to shareholders. Many CEOs inheriting an overleveraged company in the midst of COVID would have simply pursued dilution, blamed COVID and previous management, and continued to lead a now properly capitalized company without suffering from the dilution themselves.

If we focus back on the price-chart, it becomes evident that all of this has worked out very well for the equity and the brave souls who bought it during the Covid-lockdowns. The market cap hit lows of £100m and frequently traded around the £150m market cap range. With today’s price at around £300m market cap, the performance looks impressive, with some investors earning between 100-200% in 1 to 2.5 years. Moreover, the stock has now returned to the range it was before Covid, following a disappointing 2019. On the surface, one might conclude that the stock is now roughly fairly valued, and the recovery is complete. However, this conclusion overlooks a major factor in the price, namely, the significant debt reduction and deleveraging of the equity. Therefore, if we shift our focus from the market cap of the business to the TEV (market cap + net debt), a whole different story emerges:

The company's total enterprise value (TEV) is a better way to price a business as it takes into account debt and other parts of the capital structure. From this perspective, most gains in the Card Factory price have come from debt paydown, and the business is still far below pre-COVID levels. It's important to note that this graph likely understates how low the TEV currently is since it doesn't include the financials for the first half of 2024, which have already concluded but are not yet known. This first half of the year should probably generate more cash, further reducing the TEV.

In my opinion, the company is in a much better position under the new CEO, who has implemented a credible, low-risk growth plan. Additionally, the company is benefiting from a reduction in competition as major competitors are grappling with significant issues. This leads us to the second element of Joel Greenblatt's magic formula: Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). This metric is used by Joel to indicate a company's level of quality. While there have been criticisms that this approach sometimes favors cyclical stocks at the peak of their cycles, I believe that the fundamental concept of purchasing high-quality companies at low prices remains sound.

So, does Card Factory align with the characteristics of a good company?

YES! A Quality Company

Let's start by discussing the mechanicall aspect that Joel Greenblatt considers: ROIC. A cursory examination of the company using financial data providers reveals an ROIC of 15%. While this might seem acceptable, it paints a misleading picture due to Card Factory's substantial legacy goodwill entry on the balance sheet amounting to £313 million, which is close to the size of the market capitalization. This goodwill item distorts the equity used by most financial data sources in computing ROIC. The legacy acquisition made by prior management is irrelevant when evaluating the ROIC for the company's internal projects and, consequently, its true ROIC. Thus, our focus shifts to assessing the return on tangible assets, for which Joel proposes the following formula in his value investing classes:

ROIC = (EBIT / (Net Working Capital + Net Equipment)) * 100%

For the past year, Card Factory recorded £55 million in EBIT. Calculating Net Working Capital:

NWC = (Total Current Assets - Total Current Liabilities) = (£75 million - £120 million = -£45 million, excluding the short-term portion of the debt or else total current liabilities would have been £170 million.)

Net Property, Plant & Equipment amounts to £132 million.

Substituting these values, we find:

ROIC = (£55 million / (-£45 million + £132 million)) * 100% = 63%

Many companies aspire to achieve returns on equity in the 20% range. Remarkably, Card Factory accomplishes 3x this with its tangible capital deployed in the business. By employing a similar approach to the return on equity calculation—excluding goodwill—we discover that due to Card Factory's limited tangible equity, even after substantial deleveraging, the return becomes either negative /infinite.

However, ROIC is a mechanical and retrospective measure of quality. Many individuals have posed the question: why does this company continue to thrive? Who still purchases greeting cards? These concerns often revolve around the potential terminal value of Card Factory, given that it operates within an industry that numerous people perceive as declining.

The UK greeting card market has been undergoing a gradual contraction for quite some time, primarily at a rate of 1-2% annually in terms of volume. Despite this decline, much of it has been counterbalanced by price increases, resulting in the market's overall value remaining relatively stable. Moreover, juxtaposed against this backdrop of diminishing volume, Card Factory sustained two decades of growth before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, even though the greeting card market might not be characterized by strong tailwinds, Card Factory seems to be positioned well to navigate these challenges.

Certainly, other remarkable companies have thrived in declining markets, and one prime example is Starbucks. Despite the ongoing decrease in US coffee consumption, Starbucks managed to rise and become one of the most globally recognized brands. It's worth noting that while a shrinking market can pose challenges, there's potential for innovative strategies to overcome them.

Another relevant case study is GameStop, which attempted to counter its decline by diversifying into adjacent products like figurines. This move could be interpreted as a sign of distress. Now, considering Card Factory's venture into gifts, a comparison arises. To me, the shift toward gifts appears more organic than GameStop's pivot. Unlike gamers universally embracing figurines, not every gaming enthusiast has an affinity for them, and the profitability per sale tends to be similar. Conversely, nearly every individual who purchases greeting cards will also require gifts throughout the year, often within the same timeframe. Notably, the profit per sale on a substantial gift is generally higher than that of a solitary card.

By refining store layouts and expanding gift assortments, Card Factory can confidently work to increase the average basket size. This approach seems to align better with the natural shopping habits of customers, unlike GameStop's move, and has the potential to drive sustainable growth.

I believe the best comparison for Card Factory, a company in a declining industry, would be Barnes & Noble, the large physical book retailer. Despite the decline in book purchases due to a combination of fewer readers and the rise of new technologies like e-books and audiobooks, Barnes & Noble managed to survive and maintain positive cash flow. This success can be attributed to their strategic decisions. Although physical book sales were decreasing, the reduction in shelf space was even more pronounced. Remember the time when most grocery stores used to have a dedicated book aisle? In response to this challenge, Barnes & Noble did make a significant misstep by investing substantial sums of money in new technologies like the Nook, an e-reader meant to compete with Amazon's Kindle.

Card Factory finds itself in a situation reminiscent of B&N, facing a declining market and competition from fresh online entrants like Moonpig. However, much like B&N, the reduction in shelf space is outpacing the decline in actual demand. This trend is exemplified by the failures of Paperchase and the substantial store closures of Carlton Cards. This decline in shelf space is mainly felt by the other big two greeting card wholesalers who raise prices to counteract this. This further strengthens Card Factory's cost advantage

In response, Card Factory has communicated its focus on transforming into an omni-channel retailer, with a heightened emphasis on the online aspect. Could this be their equivalent of the Nook? My perspective is that it is not. Omni-channel retailing is a well-established concept, unlike the Nook, which was a bet on a new technology. The company's delayed adoption of click & collect orders and the lack of centralized knowledge about store inventory in the past underscore the previous under-management.

The investments directed toward omni-channel retailing might impact free cash flow over the next two years, but I firmly believe they are a worthwhile endeavor. As previously mentioned, omni-channel retailing has a proven track record, making it a strategic move rather than a speculative technology gamble.

This investment will also empower Card Factory to directly compete with Moonpig and demonstrate its superior capabilities. Once Card Factory's online infrastructure is fully operational, I am confident that it will present a more appealing value proposition, even for online shoppers. While both companies offer a similar range of products, Card Factory boasts notably better pricing. Additionally, Card Factory's physical store network contributes to brand recognition, facilitates same-day pickups, and simplifies returns—an advantage Moonpig lacks.

As of now, Moonpig carries a premium valuation with a revenue-to-total enterprise value ratio of 2x (CARD is 0.8). This is notable because Moonpig has lower margins compared to Card Factory. Moreover, when we scrutinize their respective balance sheets, Moonpig's financial standing appears considerably weaker, which raises further questions about the disparity in valuation.

to cwrap up this section I believe eventhough the greeting card market is in a slow decline, Card Factory beeing the clear market leader and multi-year value for money retailer in the UK shoudl stil be consider a high quality company. Which is also shown by it incrediby high ROIC and infinte return on equity.

Conclusion & Investor Yield

To synthesize these elements, I firmly believe that Card Factory embodies the essence of a true "magic formula" stock, with a pronounced emphasis on the term "magic." The stock presents itself as attractively priced, showcasing a favorable EV/EBIT ratio, while simultaneously exuding a clear aura of high quality. Moreover, the presence of adept management, along with a well-conceived low-cost and low-risk growth strategy, further bolsters its appeal.

Illustrating the concept of how a low-cost, high-quality stock can conjure magical returns for investors, I intend to outline my approximation of the company's shareholder yield. This composite figure encompasses all the contributing factors that drive returns for equity holders, including earnings per share (EPS) growth, dividends, and potential multiple expansion.

Card Factory's revenue guidance projects reaching £60 million in sales by FY27 (in the year 2026) with a 15% margin. While it's plausible that they will achieve this benchmark, for a more conservative estimate, I'll extend the timeline to 8 years instead of the suggested 4. This projection yields an 8% yield from EPS growth.

Adopting a prudent stance, I assume that Card Factory can reasonably sustain an annual dividend of approximately £30 million, contributing an additional 8% yield.

Considering the aspect of multiple expansion (or contraction), and observing Card Factory's current P/E ratio of 8, I hypothesize that over an 8-year period, the company could gravitate toward a more typical market multiple of 16. This envisaged shift adds another 9% to the yield.

Pooling all these facets together, the composite emerges as follows:

A: EPS Growth: 8%

B: Dividend: 8%

C: (A+B) Fundemental driven yield: 16%

D: Multiple Expansion: 9%

E: (C+D) Total expected shareholder yield: 25%

Even excluding the effect of multiple expansion, the stock is poised to surpass expectations, with the joint influence of EPS growth and dividends already yielding an impressive 16%. This robust performance underscores the likelihood of a stock reevaluation. If we introduce the aspect of rerating as well, the cumulative yield escalates to 25%. This underscores Card Factory's potential to deliver substantial returns to investors.

I'd like to emphasize that my earlier assumptions are intentionally conservative. To underscore this point, I've extended the timeframe for achieving growth targets by a factor of two. Additionally, the estimated dividend figure I provided is intentionally conservative, representing a low-ball estimate. Furthermore, I firmly believe that a price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple of 16 might be underestimated for Card Factory, considering its high-quality attributes. The market, while not perfectly efficient, is expected to recognize this sooner than the originally projected 8-year period.

This is how I think of CARD. Collect dividend while you wait for valuation to reach precovid levels. Valuation around PE ~11-14x or div yield of ~2.7-4.8% (2017-2019).

Which is around a 100% increase from the current PE of ~6x and a theoretical div yield of ~5.5-8%.

This is how I came up with my dividend numbers.

They stated in their 2023 annual report, "the Board envisages recommencing dividend payments at a level of 2-3x dividend cover based on profit after tax, subject to a Leverage ratio assessed across the financial year of not more than 1.5x (excluding lease liabilities) being maintained after the distribution is made."

Net Income LTM ~ $66 million

$411 million market cap

3x-2x Dividend Cover = ~ $22 million dividend - $33 million dividend, 22/411 - 33/411 5.4% - 8% div yield.

This to me is also conservative as I expect FY24 net income to be higher than LTM.

Great research and article Iggy