Nova Ljubljanska Banka The Cheapest Bank in Europe?

A deep dive in to Slovenia's largest and Europe's cheapest bank

Warning: The following article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice. The author is not a registered financial advisor and does not provide investment recommendations. Any investment decisions you make should be based on your own research and analysis.

Additionally, please be aware that the author may have a financial interest in the securities discussed in this article. The author reserves the right to buy or sell any security mentioned in this article at any time, without prior notice. Therefore, the information presented in this article should not be considered as a solicitation to buy or sell any security. Please consult with a registered financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Pitch Summary

NLB is the largest bank in the Republic of Slovenia and a major player in the South Eastern European market. I believe the stock is exceptionally undervalued, given its outstanding performance since being privatized and going public in 2018. Over the last five years of being public, NLB achieved an average return on equity of 14%. However, today the bank trades at only 0.59 of its book value and has a trailing twelve-month PE ratio of ~4x in the current higher interest rate environment.

Even in a low/negative yield environment, which is typically unfavorable for banks, NLB has managed to achieve ROEs of above 10%. So, even in a worse rate environment, the bank trades at a PE of approximately 6x. Furthermore, the bank currently offers a dividend yield of 6%, which I expect to grow, providing solid downside protection.

The apparent and readily identifiable undervaluation might suggest that NLB has a risky balance sheet or capital structure. However, this is not the case. NLB boasts a highly liquid, short-duration balance sheet and a low loan-to-deposit ratio, made possible by its low cost and stable deposits. I believe there are three other key reasons that might explain why NLB's stock is undervalued, all of which I'll discuss in more detail:

The bank's likely undervaluation stems from its poor historical performance during the financial crisis. This appears unjust, considering the significantly less risky balance sheet it currently maintains compared to pre-2008. Moreover, there has been a change in management; the new team, in place since 2016, has done an excellent job of steering the company while minimizing risks.

Another factor contributing to the bank's undervaluation is its substantial exposure to post-Yugoslav countries outside the EU, which are often perceived as riskier. However, NLB stands out as a conservative underwriter in the region, consistently achieving lower non-performing loans (NPLs) than the market average in all core strategic markets. Additionally, these markets exhibit lower ratios of bank assets to GDP compared to more developed European neighbors. Paired with generally higher economic growth, these factors position these markets as among the few where I confidently predict growth in the banking sector.

Finally, NLB went public in 2018 after being owned by the Slovenian state, which still holds a 25% plus 1 share interest. The share structure involves slightly more than 50% of the shares being traded through a GDR on the London Stock Exchange. This structure, combined with the substantial ownership stake of the Slovenian government, renders the stock much less liquid than one might anticipate for a large bank

Finaly, I think the NLB offers a lot of upside as it’s trade for 0.59 book value even though I expect it the be able to consitently earn a return on equity wel above 10% for the forseable future. For that reason it should probably rerate closer to other high quality bank peers from eastern europe. While waiting for this rerate you wil catch a very substantial dividend.

The rest of this article will be structured as follows:

1. History of NLB & Slovenian Banking Sector

1.1 Early history - Collapse of Yugoslavia 1820-1991

1.2 Post Yugoslavia War - Financial crisis 1991 - 2008

1.3 Financial/Euro crisis and restructuring 2008-2018

1.4 Re-privatization 2018-Present

2. Management

3. Business model & Performance

3.1 Funding

3.2 Assets

3.3 Complete balance sheet

3.3 Non-interest income

3.4 Cost control

3.5 Returns on assets and leverage

3.6 Growth & Capital allocation

3.6.1 Acquisitions

3.6.2 Dividends

3.7 Taxes

3.8 Putting it all together

4. Slovenian & SEE economy

5. Slovenian banking market/Competion

6. Share structure

7. Comparables

7.1 Slovenian stocks

7.2 European banks

8. Looking forward & Valuation1. Overview and History of NLB

NLB is the largest banking group headquartered in Slovenia and ranks shared first in market share (30%), following a recent merger that positioned OTP also with a market share of 30%. NLB also holds a strong presence in several other South Eastern European countries, with a market share of 10% or more in all of them, namely Serbia, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Montenegro.

The entire banking group operates through 428 branches, managing €24.7 billion in assets and serving 2.7 million clients. Active in retail banking, corporate and SME banking, as well as wealth management, NLB has an interesting yet checkered history that is important to understand in order to grasp the current state of the bank. The following passages will briefly cover this controversial history of NLB.

1.1 Early history - collapse of Yugoslavia 1820-1991

The year 1820 marks the inception of banking in the Slovene territory, with the establishment of the Carniola Savings Bank. Following World War I, Slovenia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1919, Ljubljanska banka was founded, the clear predecessor of NLB. This bank swiftly became the largest in Slovenia, playing a crucial role in the country's economic development during the interwar period.

After World War II, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia transformed into the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). Ljubljanska Banka, along with all other banks, was nationalized to operate as a state-owned bank. Despite continuing to play a significant role in the economy during this time, the evident challenges were associated with the limitations of communist central planners in the realm of banking.

The communist era for SFRY concluded with a series of bloody conflicts that led to the independence of Slovenia in 1991. Ljubljanska Banka became separated from the central bank of the SFRY and continued with all its previous assets. Importantly, not all previous liabilities were retained, notably affecting Croatian customers who lost their savings at Ljubljanska Banka in this process. This has resulted in a prolonged series of lawsuits from Croatian banks against Ljubljanska Banka and later NLB to recover these savings, plus interest.

1.2 Post Idenpendce - Fincancial crisis 1991-2008

From 1991 to 1994, Ljubljanska Banka and the broader Slovenian banking sector underwent a period of restructuring and adaptation to the new capitalist market system and democratic politics. A heritage of political interference in financing during the communist era left many banks with overexposure to bad loans in unprofitable companies. Furthermore, high inflation led to many loans offering inadequately low yields.

In 1994, Ljubljanska Banka transformed into its current form, Nova Ljubljanska Banka (creatively named "New Ljubljana Bank"), by the Slovenian government. This transformation involved taking over a large part of the assets and liabilities of Ljubljanska Banka. From this moment until the 2000s, NLB focused on consolidating its leading position in the Slovenian market.

In 2001, the government of Slovenia adopted a privatization plan for NLB (which operated as a profitable company but was fully owned by the Government of Slovenia). The first phase of privatization concluded in 2002, with a 34% stake being purchased by the Belgian KBC group and a 5% stake by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Furthermore, from 2000 to 2008, NLB concentrated on expanding its business in the rest of South Eastern Europe (mainly former SFRY countries, except Croatia due to ongoing lawsuits). Analyzing NLB's financials from 2002 to 2007, it appears as a rather mediocre bank with an average Return on Equity (ROE) of 10.7% over these years, while using significant leverage, as Return on Assets (ROA) was consistently above 1% for only one out of these six years.

Notably, Slovenia also joined the EU in 2004 and adopted the euro in 2007, right in time for the worst set of crises since the Great Depression of 1929.

1.3 Financial/Euro crisis and restructuring 2008-2018

NLB and the broader Slovenian banking sector experienced significant increases in non-performing loans (NPLs) during the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent euro crisis in 2009, with NLB reaching a peak of 32% NPLs in 2012.

It's important to highlight that all Slovenian banks fared poorly during the financial crisis, necessitating a bailout from the Slovenian state for NLB and the other two largest banks, while two smaller banks were liquidated. It's worth noting that Slovenia and NLB were particularly vulnerable to the financial and euro crises due to their fast economic growth following the adoption of a market system, accelerated by joining the EU. The Slovenian economy, heavily reliant on exports, primarily directed towards local neighbors like Italy (How is that for you main trading partner in 2008?), faced challenges.

From the onset of the 2008 crisis, NLB initiated efforts to simplify its corporate structure and reduce the number of companies within the group, concurrently reinforcing its internal control systems. Starting in 2010, NLB's focus shifted towards divesting non-core subsidiaries. Despite these measures, the bank found itself in need of several capital raises.

The first occurred in 2011, amounting to a 250 million euro capital raise, with 97.35% of the funds provided by the Slovenian government. In 2012, additional capital was acquired by selling a 320 million euro hybrid loan to the Slovenian government and issuing 61 million euros in shares. During the same year, the Belgian KBC group divested its stake to the Slovenian government, fully returning NLB into state ownership. In 2013, the hybrid loan was converted into equity as triggered by conversion conditions. The final and largest capital raise took place in December 2013 when the Slovenian state augmented NLB's capital by 1.5 billion euros.

Additionally, a significant portion of toxic assets, valued at 2.2 billion euros, was transferred to a state-led restructuring fund. In return, NLB received loans backed by this fund but guaranteed by the Slovenian government. In total, NLB received approximately 2.2 billion euros in state-infused equity from 2011-2013, not a pretty picture.

The transformations aimed at simplifying the structure of the group and focusing on core activities began to yield positive results in 2015, 2016, and 2017. All core group members were profitable during these years, and the NLB group achieved a record profit of 225 million euros with a Return on Equity (ROE) of 14.4% in 2017.

1.4 Re-privitzation 2018 - present

In November 2018, the Slovenian government initiated the process of re-privatizing NLB by conducting an initial public offering (IPO) of the stock on the Slovenian market and introducing Global Depositary Receipts (GDRs) for trading on the London Stock Exchange. The Slovenian government divested 59% of their shares in 2018 and further reduced this stake to 25% plus 1 share in 2019. It's noteworthy that this 25% + 1 share still grants the government significant influence over the company, allowing them to block proposals that require a 3/4 majority.

As the CEO articulates in the quote above, NLB has truly excelled since privatization, demonstrating impressive performance since 2018. With two succesfull acquisitions under its belt, the bank finds itself in a more favorable position than ever before.

The current management has been in place since 2016 and has contract for their roles until 2026. With this context of NLB's historical challenges in mind, the remainder of this article will primarily focus on the performance of the bank under the current management and how its transformed business model is well-positioned for current and future economic situations.

2. Mangement

NLB’s management board is spearheaded by three individuals who have all been part of the management board since 2013 or earlier. This means that all three of them have played a crucial role in leading the company through its restructuring phase, and they now collectively boast a 10-year track record that we can study. To start with, the CEO Blaž Brodnjak (49 years old), joined the management board in 2012 in his role as Chief Marketing Officer (CMO). He became CEO in 2016 and also retained his role as CMO until 2022. This shows that he has a pretty serious work ethic because he was CEO and CMO for four years. After relinquishing the CMO role in 2022, this responsibility was split between two people. Note that the term CMO may give the wrong impression; he is not just a marketer but more of a strategist, which is also his main responsibility as CEO.

He has 22 years of experience in management positions in banks and has been part of the supervisory board of 13 banks in 6 countries, three insurance companies, and a leading wealth management company in Slovenia. Furthermore, he was named Manager of the Year in 2022.

Secondly, the Chief Risk Officer (CRO) Andreas Burkhardt (52 years old) has been in his current role since 2013. He is the key individual responsible for reducing NLB’s NPLs and improving the company's processes around restructuring, aiding corporate clients in financial troubles.

Lastly, Chief Financial Officer (CFO) Archibald Kremser (52 years old) has also been in his current role since 2013. He has played a key role in improving NLB’s internal control, as well as modernizing the bank, and he is chiefly responsible for the IT systems.

Currently, the three of them are compensated almost equally, which I find interesting, as most companies tend to reinforce the hierarchy between management board members by paying the CEO significantly more than the rest of the management board. All three of them earned roughly ~620 thousand euros in 2022, of which roughly ~500 thousand was base salary, and the rest was variable.

All three of them own relatively few shares compared to their salary, although the fact that they even own shares (that they bought during the IPO) is already a good sign in Slovenia, a country with little history of investing and share ownership. The CEO currently holds 1,700 shares worth ~137 thousand euros. The CRO holds 800 shares worth ~64 thousand euros, and the CFO holds 791 shares worth ~63 thousand euros.

It is interesting to note that at the time of the IPO, all three of them earned just around 170 thousand euros each, so at the time, they did commit a decent chunk of their salary to the IPO. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that all three of them have worked in these management positions relatively long from 2013 to 2017 for relatively little pay given the demands of restructuring a major bank. I do think this fact reflects really well on these three gentlemen.

Lastly, as ill aim to show in the next section where I’ll focus on the business model and it’s performance I’ll hope to show that the management has done an excellent job of turning a poorly run bank with a checkered history and to a well run bank with a great future.

3. Business Model & Performance

NLB, being a bank, has many moving parts to its business model, and perhaps most importantly, it revolves around how it's funded and the type of assets it holds. As I'll show, NLB has an excellent focus on attracting low-cost deposits, significantly reducing its all-in cost. Consequently, it has been able to achieve high profitability while taking relatively little risk and maintaining a low loan-to-deposit ratio. The remaining assets are strategically placed in more liquid government bonds or held at the central bank. This, coupled with effective cost control, enables NLB to earn satisfactory returns in a low-rate environment and exceptional returns when rates are higher.

I’ll break down all part of the bank in the following sector and them put them all back together in the end.

3.1 Funding

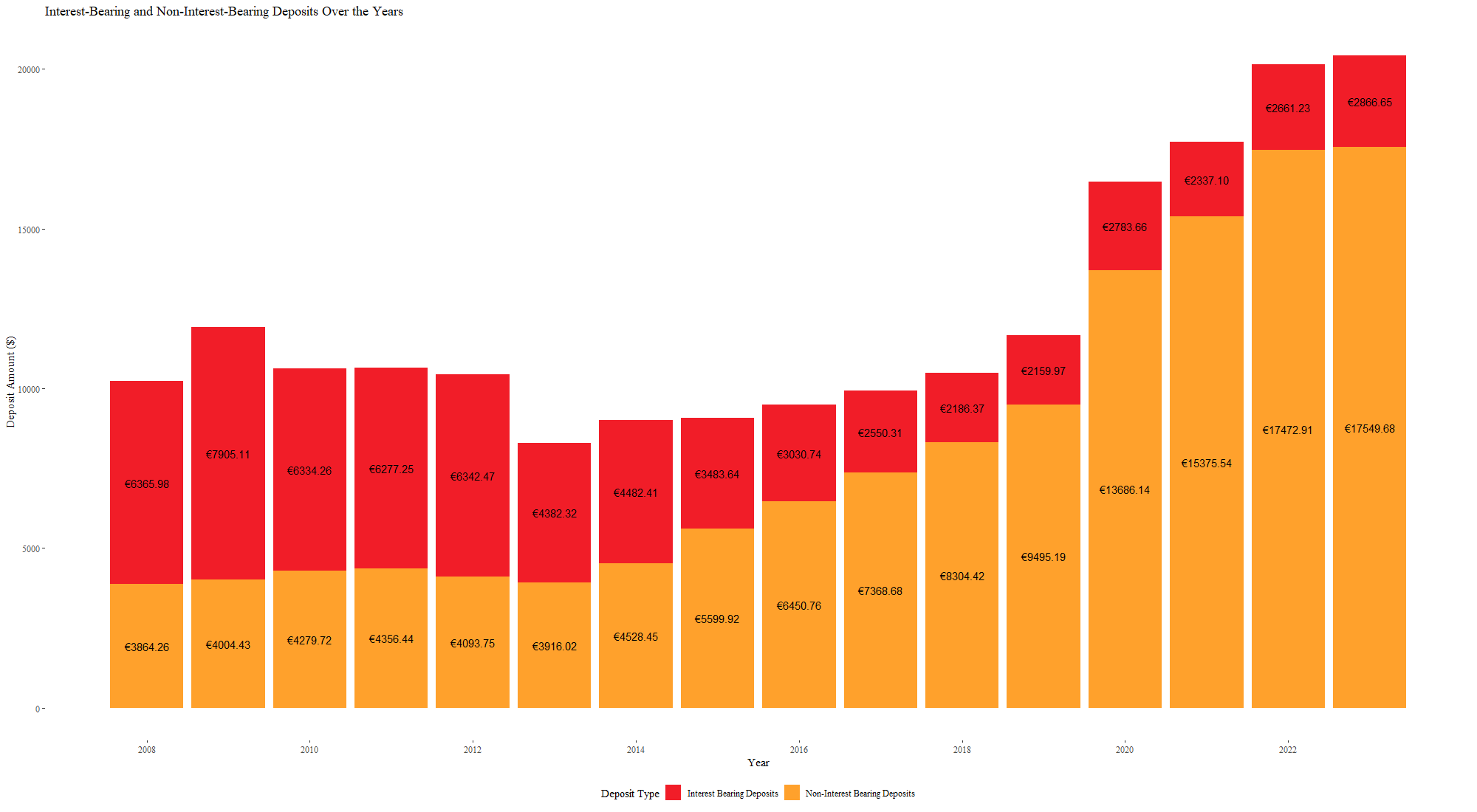

Funding, or more precisely deposits, is probably the most crucial aspect of a bank and the area where it is easiest for a bank to build a sustainable advantage. NLB is no different. As of Q3 2023 the interest cost on NLB’s 20b in deposits was just 0.34%. Over the period following the financial crisis and the subsequent low-interest-rate environment, NLB has been very successful in convincing almost all depositors to transition from demand/savings accounts to sight/checking accounts. This has resulted in NLB having a large share of very inexpensive deposits.

NLB has successfully attracted more and more low-yield deposits in recent years by focusing on customer service and retail solutions. Zero interest on checking accounts is not uncommon in Europe, where central bank rates have even gone negative. However, in most major Western European countries, banks have started offering interest on checking accounts again in 2022. This is not the case (yet) in Slovenia, highlighting that Slovenian checking account rates are even more inelastic than those in other countries.

During the low-rate environment, NLB even attempted to minimize inflows from large corporate customers by charging higher fees for accounts with a lot of money in them (similar actions are not allowed for retail accounts). With rates rising, NLB has once again removed those fees as they feel they can generate a good spread on these extra deposits once again.

Although there is no way to be sure about why Slovenian deposits are even more inelastic than those in other European countries, there are a couple of possible explanations. Firstly, the Slovenian banking sector is one of the most oligopolistic ones, even by European standards (the top 2 banks have an 60% market share). Secondly, all of these banks have relatively low Loan-to-Deposit (LTD) ratios, which means they do not necessarily have much need for extra deposits. Lastly, Slovenia is a post-communist country that likely has a less financially educated population. Furthermore, the Slovenian population is, on average, much less wealthy than Western European countries, meaning the average account size is smaller. For example, NLB only offers interest rates on amounts above 1000 euros. This is even more relevant for the other SEE (South Eastern European) countries that are even less economically developed. With many small accounts, fees and services are probably much more important to many NLB customers than the interest on checking accounts.

The second pillar of NLB’s funding comes from long term wholesale funding, I like this type of funding a lot less and it is much more expensive especially compared to NLB’s deposits. NLB uses this type of funding because it’s is part of a type of regulation called minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL). As of Q3 NLB had 1.564b in long term debt outstanding, with an average interest rate of 6.91% (Most of this interest rates reset in 5y intervals).

Although this funding represents a tiny part of the capital structure, it currently constitutes more than half of the current interest costs. NLB is currently comfortably in compliance with their MREL requirements, so I do not expect them to continue the increased share of wholesale funding seen in recent years.

The last remaining major part of NLB’s funding is, of course, the equity, which is currently 2.8 billion. This structures NLB's liabilities as follows:

Deposits: 80.7%

Debt: 6.1%

Equity: 11%

Other: 2.3%

The total cost of NLB liabilities (non-equity) is currently 1.08%. With the European Central Bank rate at 4.0% for bank deposits, this means NLB can earn a very comfortable spread by depositing money at the ECB. This low cost of funding has allowed NLB to maintain a very safe yet profitable set of assets on the balance sheet.

I do expect the funding cost to keep increasing if interest rates stay higher, but I am very comfortable with NLB’s current funding position.

3.2 Assets

NLB’s earnings assets are very interesting, characterized by high liquidity due to a large share of government bonds and cash at the central banks combined with above-average underwriting for the region. I believe NLB runs a fairly conservative balance sheet.

As of Q3 2023, NLB holds 4,653m in financial assets, 6,334m in cash (of which ~5 billion is with the Central banks), and 13,666m in loans to customers. These loans are divided 50.9% (6,955 billion) to corporations and 46% (6,355 m) to individuals, with the remaining 2.6% being to the government. With 44% of the assets (financial + cash) being highly liquid, NLB has one of the most liquid balance sheets around, giving them a lot of flexibility.

The 4.653 m financial assets of NLB consist of 75% government bonds, 12% unsecured bank debt, and the rest is made up of other types of publicly traded non-government debts. I really like this large liquid, low-risk position on the balance sheet. Some of you might point out that although government bonds might seem lower risk than loans a bank can write, they were key to the demise of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). However, NLB’s bond portfolio is importantly different from that of SVB, as SVB got caught out chasing yield and taking too much duration risk (they mainly held US 10 years). NLB’s average duration on the bond portfolio is less than 3 years, making this a relatively low-risk position in terms of interest rate risk.

Then we have the 6,334 m cash position. Of this cash, 5 billion is stationed at the central bank. Normally, banks don’t really earn a satisfactory spread by putting money at the CB, but due to NLB’s inelastic low-cost deposit base, NLB can earn a very nice spread even by putting money at zero risk at the CB. As NLB’s funding cost stands at 1.08%, yet it can put money at the CB at 4%, a 3% spread at zero risk is very good business. This huge cash position is, in my opinion, absolutely key to de-risking NLB’s balance sheet.

Finally, the interesting part: the 13.666 billion loan portfolio of NLB. Bad underwriting is absolutely why NLB got into problems after 2008. However, NLB has become a much better and more conservative underwriter in the meantime. While growing the volume of loans, NLB’s current management has been absolutely great at getting NPLs down (currently NPL ratio is 2.2%).

Over the last 6 years, NLB has consistently maintained lower Non-Performing Loans (NPL) in all their core markets (See Appendix A), except in Slovenia (where they constitute one-third of the market), where they consistently hover around the average. I believe this speaks volumes about the risk management practices of the current management.

This is further exemplified by the consistently low loan-to-deposit ratio. The fact that the bank puts a lot of cash in financials or at the central bank shows they are diligent in underwriting. If they cannot find a risk they like by writing a loan, they will put it into a low-risk liquid asset.

NLB’s credit portfolio is split roughly 50% between Slovenian and other SEE markets. It comprises 29% mortgages, 22% retail consumer, 28% SMEs, and 21% corporate. 51% of the portfolio is fixed rate, so 49% of the portfolio has been benefiting from higher rates directly. I find this quite impressive, considering most people were aware of the low-yield environment and tried to lock in low yields in previous years in Europe.

If we combine liquid assets and the 49% of loans that are floating rate, and add in new loan formation, NLB is very well positioned to keep benefiting from the high-rate environment. On the flip side, the portfolio will start earning less quickly if interest rates drop.

The corporate credit portfolio is well diversified across industries, although both manufacturing and wholesale and retail trade make up about 20%. However, both of these industries further break down into different subparts that don't seem to correlate (i.e., food manufacturing vs. electrical manufacturing).

In short, I really like the asset side of NLB’s balance sheet. It is characterized by very high liquidity and little duration risk or yield chasing. They have a very healthy and diversified loan portfolio that is roughly 50/50 fixed vs. floating rate interest. Most importantly, the current management has done an excellent job at reducing NPLs and becoming one of the best underwriters in the region.

This hopefully adresses point 1 from the intro regarding the 2008 performance, as NLB now is a good underwriter and has a very safe balancesheet so 2008 will not be repeated.

3.3 Non-Interest Income

Like almost any other bank, NLB not only earns money through interest rate spreads but also from various fees and commission income. For NLB, these fees primarily come from cards, payments, investment funds, and bancassurance products. Additionally, there was income from a high-balance deposit fee(which was canceled in 2022).

Although the contribution of this subsidiary may not be that substantial, it is crucial to note that NLB is also the largest private bank and asset manager in Slovenia, holding approximately 1 billion in assets. This could be an interesting growth factor in the future, as the fact that the largest asset manager in the country manages only 1 billion in assets suggests that the country may be underexposed to equities.

The non-interest income can be broken down into two major elements: the aforementioned fees from banking-related services and certain line items related to trading activities and the sale of financial assets. The income from trading activities is inherently more cyclical than other parts of the bank, making it challenging to make definitive statements about it. However, over the past few years, it has consistently generated a steady profit, which is positive.

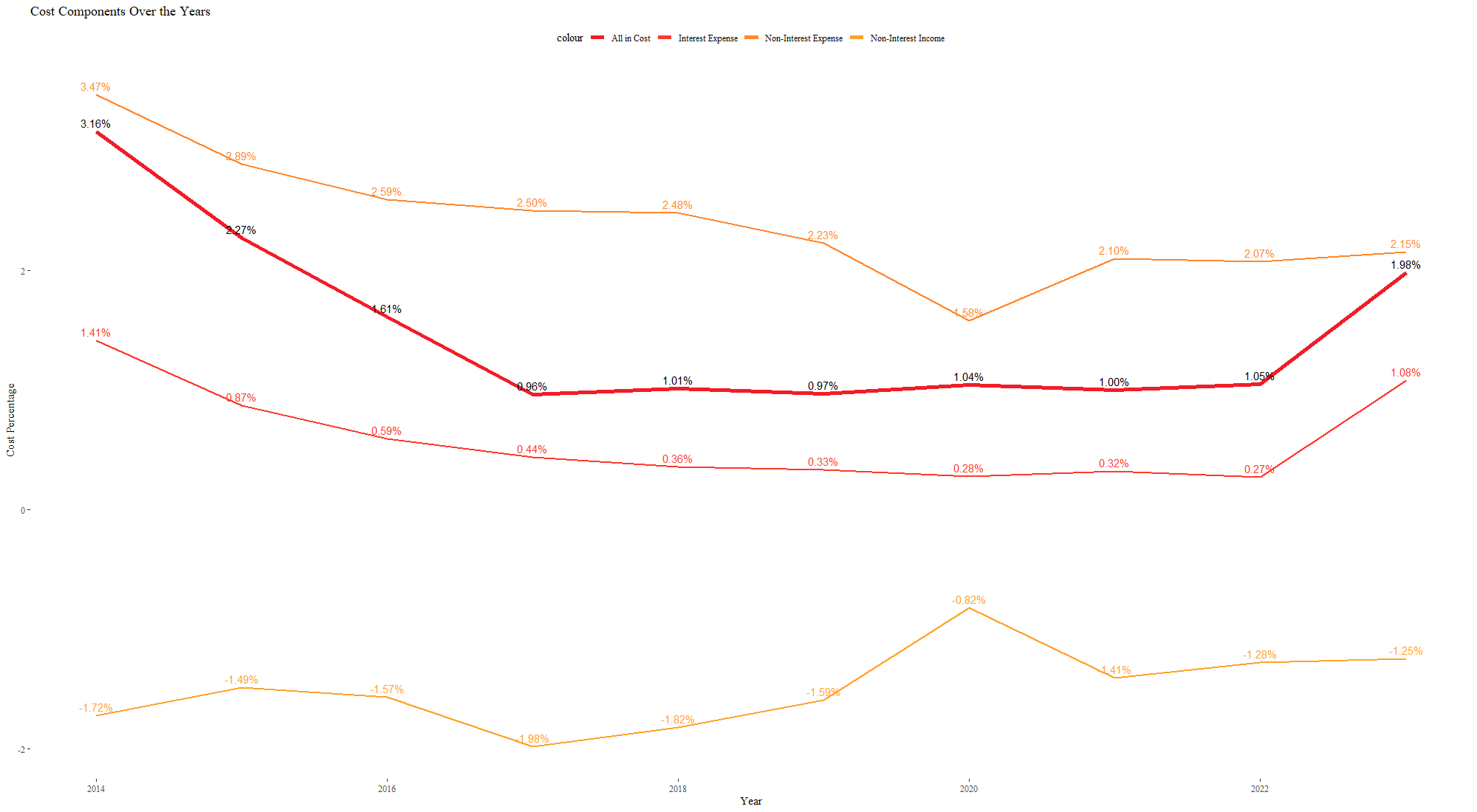

The fee component, on the other hand, is more stable and under management's control, making it worthy of a brief study. As a percentage of assets, this type of income has trended slightly downward since 2014 when it represented 1.40% of assets, stabilizing in recent years at around the 1.10% of assets level. Given the bank's growth in both assets and liabilities in recent years, observing this stable income growing in tandem with asset growth is a positive indicator.

3.4 Cost Control

In addition to securing cheap funding, effective control over non-interest expenses is another significant advantage for a bank. In this regard, the current management has demonstrated excellent performance in enhancing the bank's efficiency. They have managed to reduce non-interest expenses as a percentage of assets from 3.5% in 2014 to the low 2% range (specifically, 2.07%-2.15%) over the last three years. This achievement is particularly commendable considering that the bank absorbed two smaller banks during this period. While operating synergies over time contribute to cost reduction, which is expected, the swift and efficient realization of these cost savings reflects effective management.

More critical than just assessing non-interest costs is evaluating the all-in cost of funding. I calculate this as follows:

All in cost: Interest Cost + Non-Interest Cost - Non-Interest IncomeThe all-in cost of funding has consistently decreased under current management, reflecting their success in reducing both non-interest and interest costs. From 2017 to 2022, these costs remained remarkably low, hovering around 1%. However, a recent uptick is noted, primarily attributed to higher interest rates and the expenses related to MREL funding. Despite this increase, the all-in cost currently stands at approximately 2%, which is significantly lower than the rise in yields on income-earning assets, contributing to record profits.

The exceptional cost control measures implemented by the bank position it well to generate profits across various interest rate environments. Recent history supports this, as the bank demonstrated healthy profits in the ultra-low interest rate environment and even more substantial profits with rising yields.

Looking ahead, there appears to be potential for further cost efficiency improvements, particularly as NLB predominantly serves smaller retail customers. If the economies of the SEE region continue to thrive and residents become wealthier, this trend may lead to higher average account sizes, typically beneficial for a bank's efficiency.

3.5 Returns on Assets and Leverage

A bank, of course, makes substantial profits on equity because it provides a cost-effective means to leverage towards returns comparable to bonds. Let's delve into the leverage ratio utilized by NLB and understand how this translates from a return on assets to a return on equity.

When NLB went public following government ownership in late 2018, it operated with a conservative approach and maintained lower leverage. Subsequently, leverage was increased to more typical levels in the following years. As of Q3, NLB's equity was leveraged at 9.3x, reaching a peak of 9.7 at the close of 2021. Assuming a more normalized leverage ratio, we can analyze the bank's historical return on assets and multiply these values by our assumed leverage ratio to derive a reasonable approximation of normalized ROE.

I approach this exercise as follows:

I calculated EBIT, excluding unusual items (notably, NLB experienced two substantial accounting gains due to purchasing banks below book value, which I opted to exclude). Subsequently, I multiplied this figure by 0.87 (assuming a 13% effective tax rate, as elaborated in section 3.7) to obtain after-tax results. I then computed the ratio:

ROA: after tax earning year(t) / ((total assets (t) + total assets(t-1))/2)Using this calculation, it is evident that NLB achieved a return of over 1% on assets in all years except 2020. When applying our anticipated leverage ratio of 9.5x, we derive an assumed ROE. This results in a comfortable ROE, with the average for the period being 13.36% and 12.63% when excluding the outstanding 2023 results. Moreover, this calculation is fairly conservative as it excludes gains from acquisitions that actually contribute value to investors. It's essential to note that this entire period is characterized by a challenging low-interest-rate environment, making operations difficult for banks.

3.6 Growth & Capital Allocation

Following the privatization at the end of 2018, NLB embarked on a growth program. As previously mentioned in the discussion on deposits, this growth primarily stems from attracting more service-oriented and young depositors. Although loan growth has slightly lagged behind the increase in liabilities, particularly deposits, it has resulted in a low loan-to-deposit ratio and a high proportion of liquid assets and cash. I appreciate this type of conservative growth, as writing too many bad risks too quickly is a surefire way to undermine a financial institution.

As discussed in the funding section, NLB has successfully expanded its liabilities, primarily through the increase in non-interest-bearing deposits. Additionally, it has augmented its balance sheet by issuing a significant amount of wholesale funding in recent years to meet MREL requirements. Deposits have organically grown by approximately 7% since going public, and even more rapidly when factoring in the deposits acquired through acquisitions.

3.6.1 Aquisitions

Acquisitions have been a pivotal component of NLB's strategy since going public. As the largest bank headquartered in the post-SFRY area, with an exclusive focus on this region, they enjoy a competitive advantage in pursuing acquisitions. They have successfully completed two acquisitions, both of which I consider highly successful.

The first one was Komercijalna Banka a.d. Beograd (KBB), acquired at a discount to book value. The CEO of NLB mentioned after the deal that they were the only party seriously considering completing this acquisition, signaling that focusing on this region, significant enough for NLB but not for other major players, provides a competitive edge.

KBB was acquired for 394.7 million euros with a negative goodwill of 137.9 million euros. While the bank was purchased for 74% of book value, the merger with NLB's existing subsidiary in Serbia resulted in significant cost synergies. The combined Serbian bank is now the most profitable subsidiary after the main Slovenian bank. Before the acquisition, NLB generated 2.6 million euros in Serbia, and the results since the acquisition in Serbia are as follows:

2020: 27.5m (2.6m ex aqusition)

2021: 39.1m

2022: 66.0m

2023: 115m (expected)

----------

Total: 247mSo, in roughly four years after the acquisition, the subsidiary, which was quite marginal pre-acquisition, has already recouped 62% of the purchase price. With all cost synergies now realized and a positive tailwind from rising rates, the Serbian subsidiary stands out as a top performer in the NLB group and, in my opinion, a highly successful acquisition. It's noteworthy that the FY 2023 profit is approximately 1/3 of the purchase price, ultimately making the acquisition remarkably cost-effective.

The second acquisition involved taking over the assets of Sber Bank in Slovenia after it became insolvent following its separation from its parent due to sanctions following the Russia-Ukraine war. This subsidiary was subsequently renamed Nbank and eventually merged with NLB. NLB acquired this bank at basically no cost, registering a gain of 172.8 million euros of negative goodwill. While not the most significant acquisition, it further consolidated NLB's leading position in the Slovenian banking market.

In summary, I believe NLB has been highly successful in completing acquisitions in the SEE area, further aided by relatively little interest from other major players.

3.7 Taxes

nother aspect of corporate life that companies often have little control over is taxation. The corporate tax rate in Slovenia was 19% (recently changed to 25%). However, NLB managed to maintain an average tax rate since going private of just 5.9%. This can be attributed to several factors, including some form of non-taxable income that NLB possesses, as well as low tax rates in certain subsidiary countries. Most significantly, the large legacy tax assets NLB holds result from substantial losses incurred during the crisis. Tax assets in Slovenia are indefinite; however, they can only reduce taxes by a maximum of 50% per year. Hence, it's reasonable to assume NLB will be paying around a ~13% effective tax rate in the coming year with the new 25% tax rate.

Another crucial tax-related factor is Slovenia's proposal for a banking windfall tax to contribute to covering the damage from recent flooding. This tax proposes to levy banks for 0.2% of their assets each year. As of Q3, NLB Slovenia had 15.5 billion in assets, so this tax would cost roughly ~32 million annually.

3.8 Complete Picture

To sum it up, NLB is a well-managed bank that is experiencing both organic and inorganic growth. It distinguishes itself with very low interest costs, primarily attributed to a substantial share of sight deposits that have proven to be relatively inelastic in this part of Europe. Additionally, the management has effectively controlled net non-interest expenses, contributing to NLB's high profitability while maintaining low risk on the asset side. NLB boasts a loan-to-deposit ratio below 70%, with almost 50% of its balance sheet in cash or relatively short-term financial assets.

Examining NLB's financial performance reveals excellence. Starting with 1.6 billion euros of equity at the end of 2018, it has grown to approximately 2.8 billion as of Q3 2023, expected to reach around 2.9 billion by year-end. This represents an 11% equity compound annual growth rate (CAGR). What's even more impressive is when factoring in the dividends paid, totaling around 450 million euros (including the 100 million at the end of 2023). Adding this back to the equity, NLB has compounded at an almost 16%, highlighting substantial growth even without reinvesting dividends. Given NLB's consistent discount to book value, reinvesting dividends could have yielded an even more significant gain over this period.

Considering the 2018-2022 period as a challenging time for European banks, NLB has navigated these challenges effectively. The shift to rising rates has been favorable, especially for NLB, where the cost of funds remains relatively stable, leading to an expanding spread. Looking ahead, I believe NLB's future is even brighter than its past, with its low-cost deposits serving as a significant advantage, particularly if central bank interest rates stay above 0 in the future.

4. Slovenian & SEE Economies

I'm not a macro expert and don't base my investments on macro decisions; nevertheless, banks are closely tied to the economies of the countries in which they operate. So, let's briefly delve into the Slovenian economy and those of the other countries where NLB operates. Slovenia boasts a GDP per capita of 29,291 USD, one of the highest among post-Soviet countries and close to the EU average, though still below many Western European peers. The Slovenian economy endured severe impacts from the financial crisis, only recently surpassing its GDP peak from 2008.

This dependence is primarily due to Slovenia relying heavily on exports to neighboring European countries. Now, shifting our focus to the other post-SFRY economies where NLB is active—Serbia, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Montenegro. All these nations are non-EU members and possess significantly lower GDP per capita compared to Slovenia. Challenges in these regions include corruption, high unemployment rates, territorial disputes, and ethnic conflicts – essentially, a myriad of complex issues.

Despite these challenges, there's hope for these countries. Most of them have a long-term goal of joining the EU or at least the EU common market, given their proximity to the European single market. Progress has been made in this process, especially with the Russia-Ukraine war prompting the EU to engage with the Western Balkans. EU leaders have extended an offer of single-market access to these countries, contingent on quick reforms. Furthermore, if the requirements are met, a 6 billion euro growth package is available for the region, consisting of 2 billion euros in grants and 4 billion euros in loans. These incentives provide strong motivation for these countries to continue moving in the right direction, beyond the initiatives already in place. Generally, considering their developmental stage, these economies are expected to grow slightly faster than their EU neighbors.

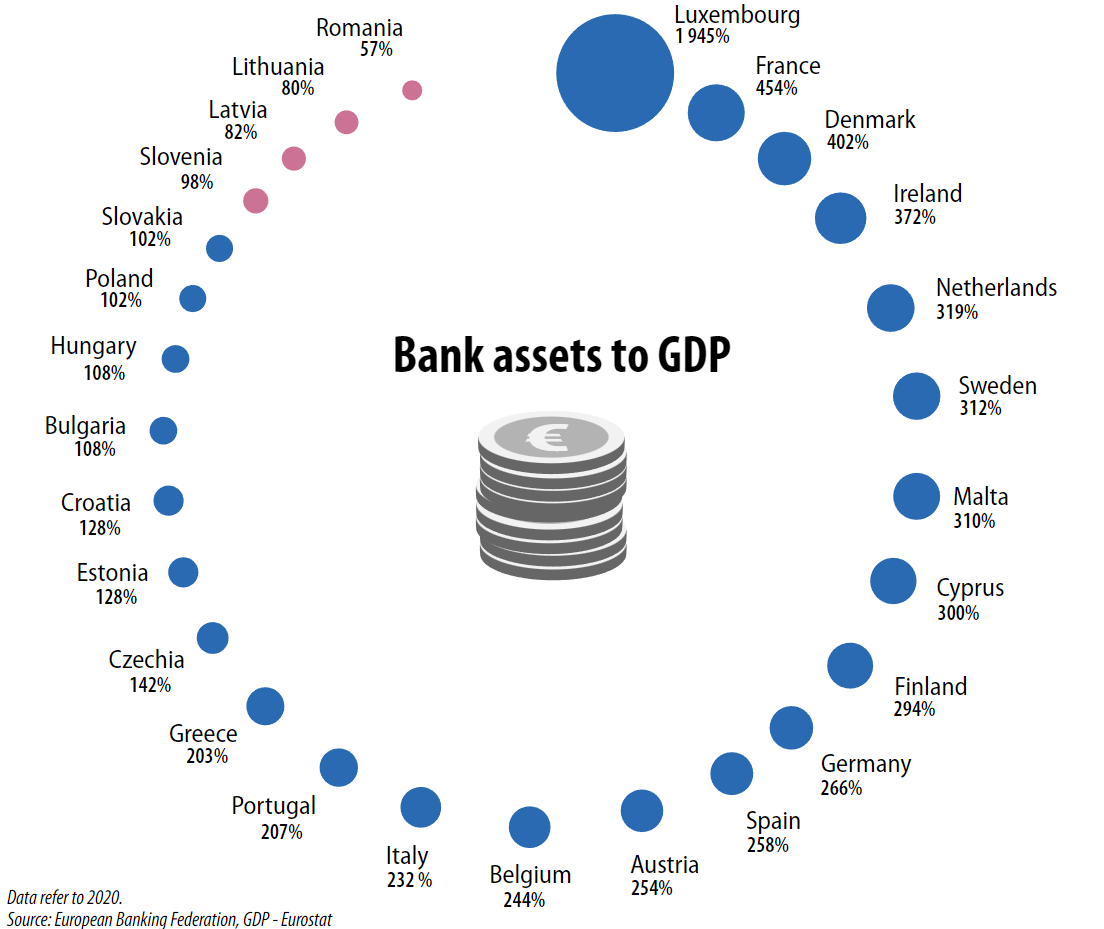

Lastly, most of these economies exhibit very low money-bank asset to GDP ratios, primarily in the low 60% range. In contrast, developed countries comfortably boast ratios well above 200%, indicating a long runway for banks to continue growing in these economies as they progress in their development.

I hope this section helped adress some worries people have around problem 2 from the intro the ecposur to the other post SFRY republics.

5. Slovenian Banking Sector (Competition)

The Slovenian banking sector stands out as one of the most consolidated globally, a characteristic shaped by a history of crises and mergers. The pinnacle of active commercial banks in Slovenia was in 1994, shortly after gaining independence from the SFRY, boasting 33 banks. The initial banking crisis in this competitive environment emerged in 1996 when Komercialna banka Triglav failed. In response, many banks formed banking groups primarily based on cooperation. However, in the late 1990s, most of these groups eventually merged, consolidating the market. A second wave of consolidation occurred during the financial crisis when the three largest banks in Slovenia came under government control due to a bailout program, while smaller banks were allowed to fail. Additional mergers during this period further solidified market consolidation.

A recent third wave of consolidation took place, with NLB merging with the much smaller Nbank. More significantly, the second, third, and fourth-largest banks in terms of market share were allowed to merge under the Hungarian bank OTP. This created two major banks in Slovenia, NLB and SKB OTP, each holding roughly 30% market share. Together, these two banks control over 60% of the market, with the new third player, Unicredit, having just a 6.6% market share.

This scenario makes the Slovenian market one of the least competitive globally. Currently, neither NLB nor SKB OTP offer interest rates on checking accounts and primarily focus on low fees and other non-interest customer benefits. Realistically, NLB and SKB OTP only need to keep track of each other's movements. This also explains why interest rates have experienced minimal movement. There's little incentive to be the first to reintroduce interest rates on checking accounts and initiate unnecessary competitive tit-for-tat, especially with no notable smaller competitors initiating such competition. In my estimation, Slovenian interest rates will likely be more inelastic than those in more competitive markets.

Another noteworthy attribute of the Slovenian banking sector is its relatively smaller size compared to GDP in comparison to its European neighbors.

This suggests that the Slovenian banking sector has the potential to sustain slightly faster growth than GDP for an extended period, especially as Slovenians become more accustomed to the use of debt markets. Additionally, it implies that the existing stock of loans is likely to be somewhat more conservative compared to other countries. This conservatism is rooted in the fact that these loans are likely backed by a larger stream of earnings, given that the entire economy is less leveraged, at least concerning bank debt.

6. Share Structure

NLB has a total of 20,000,000 shares, with 53% being held by the Bank of New York Mellon. This significant portion is then converted into GDRs on the London Stock Exchange, where 1 GDR represents 1/5 of a normal stock. The remaining 43% of NLB shares trade on the Ljubljana Stock Exchange (LJSE), where 25% + 1 is held by the Slovenian government. Consequently, NLB is traded in two places, both of which are relatively illiquid.

The LJSE, already characterized by low liquidity, is further impacted by the substantial government holding, exceeding half of NLB's float on the exchange. The GDRs on the London Stock Exchange also face challenges in terms of liquidity. It seems that there are limited investors interested in a Euro-denominated stock with exposure to almost all ex-Yugoslav countries, a low free float, and denominated in euros on a British exchange.

Presently, the double listing doesn't contribute to obtaining a better valuation for the stock. However, I believe the London listing could prove beneficial for the stock if it continues to perform well in the future.

Hopefully point 3 will seize to be a problem in the future, as it should not be hard for the stock to increase liquidity

7.Comparables

In this section, I will provide a brief overview of other stocks that appear relevant to NLB's valuation. Firstly, I will include an analysis of other Slovenian large and midcap stocks. Secondly, I will compare NLB to select European banks.

7.1 Slovenian Stock Market

Navigating the Slovenian market presents a unique set of challenges, primarily characterized by its small size and limited accessibility. The MSCI large midcap index for Slovenia encapsulates merely six companies, and NLB is a notable participant in this mix:

The largest entity in the index is KRKA, a generic pharmaceutical company with a market cap exceeding 3 billion and a dual listing in Slovenia and Warsaw, boasting a P/E of approximately 12.

Following closely is NLB, the second-largest listed company in the index, with a current market cap of 1.6 billion and a dual listing in London (P/E: 4, P/BV: 0.59).

Next in line is PETROL D.D., the National petroleum company, with a market cap just shy of 1 billion, a P/E of 15, and a dual listing in London.

Completing the index are two prominent listed insurance companies, both dual-listed in Ljubljana and London:

ZAVAROVALNICA TRIGLAV, with a market cap of €697 million (P/E: 6x, P/BV: 0.82x).

POZAVAROVALNICA SAVA, with a market cap of €376 million (P/E: 5x, P/BV: 0.92x).

The index concludes with LUKA KOPER D.D., a logistics operator from the port of Koper, holding a market cap of 427 million (P/E of 7 and P/BV 0.79x).

The broader Slovenian market comprises even smaller companies, many of which seem attractively priced on the surface. It's not challenging to find a smaller Slovenian company trading at 5x normalized net earnings. This accessibility, however, is hampered by structural issues for retail investors, as major platforms like IBRK or DeGIRO don't facilitate trading in Ljubljana. Opening a dedicated account is necessary for trading in Slovenian stocks without a dual listing.

The average P/E of other Slovenian large/mid caps is 9x, with other financials trading affordably, though not as attractively as NLB. Considering NLB's dual listing on the London exchange, substantial market cap, and commendable track record post-privatization, including the distribution of substantial dividends, I anticipate that international investors will eventually take notice. This attention should prompt a rerating to a more appropriate multiple, potentially alleviating its perceived illiquidity.

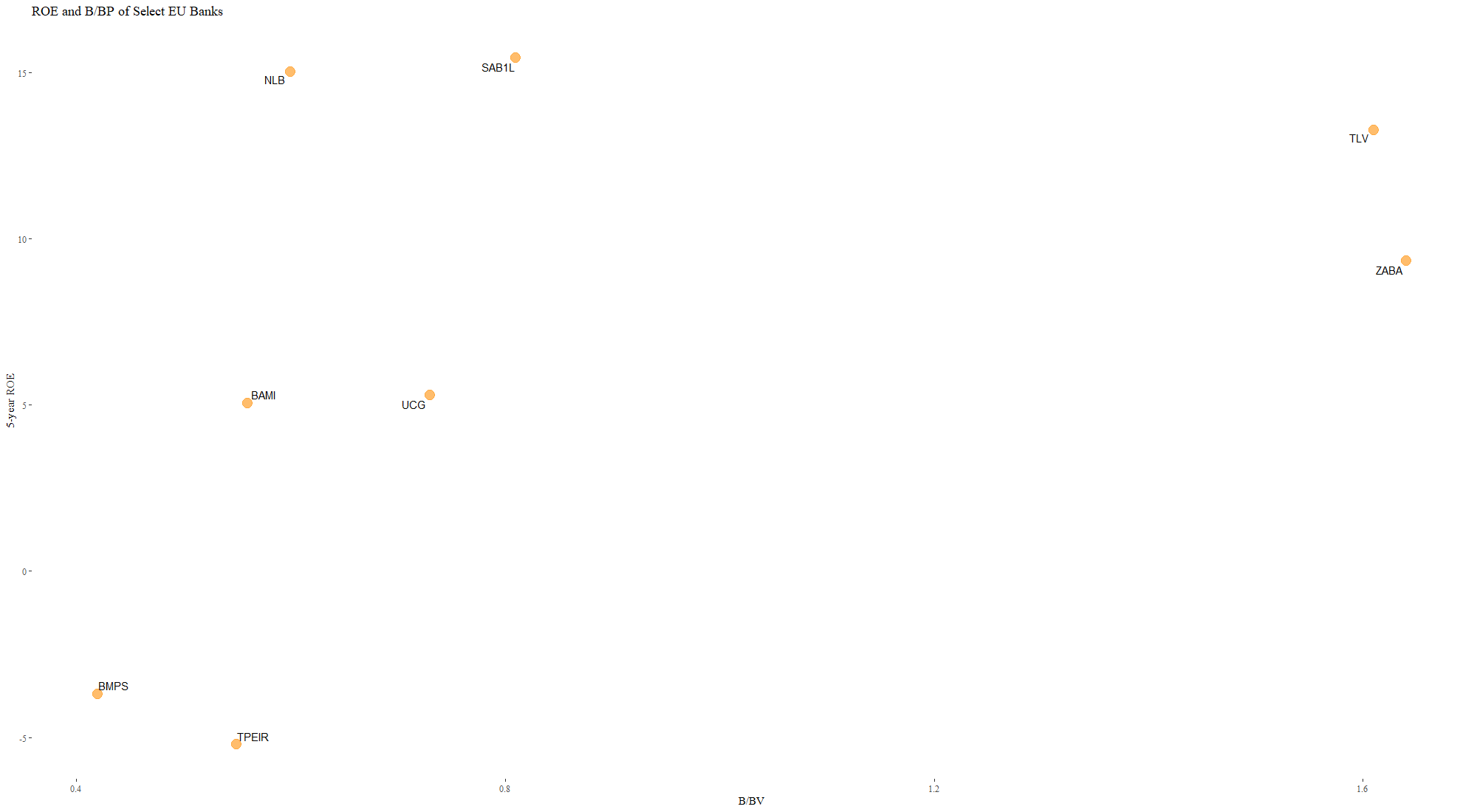

7.2 European Banks

Perhaps even more relevant than observing how other Slovenian stocks trade is understanding how other European financials fare. In the following concise study, I aim to illustrate two key points. Firstly, well-run European banks can indeed create value. To exemplify this, I selected three Eastern/Southern European banks that have demonstrated the best stock price returns (excluding dividends) over the last 10 years:

Banca Transilvania - TLV (Romania)

Zagrebacka Banka - ZABA (Croatia)

AB Siauliu Bankas - SAB1L (Lithuania)

Additionally, I've chosen banks from this region that trade at a similar book value to NLB, focusing on institutions mainly from Italy and Greece:

UniCredit - UCG (Italy)

Banco BPM - BAMI (Italy)

Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena - BMP (Italy)

Piraeus Financial Holdings - TPEIR (Greece)

For all these banks, I've plotted their current P/BV multiple against their 5-year average ROE.

This exercise aims to highlight two critical points. Firstly, European banks can indeed trade at healthy multiples and perform well. This is exemplified by a closer look at Banca Transilvania (TLV). An investment in TLV a decade ago would have compounded at 14% (in dollars), excluding dividends. TLV, excluding dividends, outperformed the S&P 500 significantly. This impressive performance occurred even without a substantial multiple rerating, as TLV traded at 1.3x book value 10 years ago. TLV's success can be attributed to maintaining a robust ROE and wisely reinvesting most of its earnings, yielding magnificent results.

Both AB Siauliu Bankas and Zagrebacka Banka have similar success stories, compounding at 17% and 14%, respectively. This underscores that a well-run bank in a growing European market remains a very worth wile business(Siauliu is actually still cheap at 0.8x book in my opinion so another palce worth digging).

Now, turning our attention to banks with comparable multiples, I'll be brief as these primarily include Italian and Greek banks that have struggled to consistently earn healthy returns on equity since 2008.

Somehow, NLB's trading patterns seem more aligned with this second group of semi-zombie-like banks rather than those that have performed well, even though NLB's performance is closer to the successful Eastern European banks. This concise study suggests that there is significant potential for NLB's stock to undergo a rerating if it continues its current strong performance.

8. Looking Forward & Valuation

Looking ahead, I believe NLB has a promising future. The company aims to pay 500 million in dividends over the next 5 years, indicating an expected annual dividend of 100 million or 65%. However, with the last quarter's earnings at 145 million, we are at a run rate of 580 million in earnings (3x PE). Even if the banking windfall tax is passed, that's 550 million. So, that's a payout ratio of only 20%. Historically, the bank has paid out much larger dividends, and I think it's risky for a financial company to grow faster than say 8-10% organically. Therefore, NLB must either find other attractive acquisitions or pay out a larger dividend.

I believe NLB will be able to keep growing at around 7-10% organically due to the underdeveloped banking markets they are active in. There are also other possibilities for growth, such as:

Expansion of their leasing operations

An entrance into Croatia (although this would be significant and politically sensitive due to legacy lawsuits)

Entrance into another SEE economy

NLB is likely overearning a bit given the current interest rate environment and the enormous lag in the movement of their cost of deposits. This will undoubtedly move up, and NLB's wholesale funding will, in part, be repriced in the coming year due to interest rate resetting on some bonds. I think NLB is very cheap, especially if we project using conservative assumptions for the next 5 years.

Assumptions for the 5-year projection:

End of year 2023 Book value: 2800 million

2023 dividend: 100 million

2024-beyond: 50% payout ratio

Banking tax: 30 million over the next 5 years

ROE: 2024: 15%

2023: 13%

2024-beyond: 11%Using these assumptions, NLB would have a book value of 4,045 million in 2028, and you would have received a cumulative dividend of 937 million (58% of the current market cap). If we assume NLB trades at a 0.9x book multiple, which seems conservative given the long track record of success for the bank and its management at that point, and I also assume you somehow just pile up your dividend, this would give a year-end 2028 valuation of:

0.9*4045 + 937 = 4983mThis equates to a CAGR of 23%. If you were to reinvest your dividends back into the stock while it still trades at a relatively deep discount to book, this CAGR will be even better, further illustrating how attractive the stock is.

Notes on downside protection: First off, if the interest rate spread suddenly collapses, even at a 10% ROE and including the new banking taxes, the stock would trade with earnings of around 250 million. That is a 6.4 PE and would still leave them in a good position to pay the 6% dividend.

Again, a big financial crisis would be disastrous for the stock (and for most others). But barring anything but a once-in-80-90 years super crisis, I think NLB is well enough capitalized and conservatively run to withstand a financial crisis. Given its good ROE in normal years, it should be able to get back on its feet rather quickly, even after a small dip.

Apendix A

The graph above shows all the NPL ratios for NLB per territory, and the NPL for the whole banking sector of that territory is reported by the local central banks.

Great write up Iggy, thank you!

I’ve been following NLB closely for the last 4 years and it’s by far my largest position. Small clarification regarding dividends – the announced payout of 500 mil eur refers to the 4 years period of 2021-2025. So far, the payout for ’21 was 100 mil and 110 mil for ’22 (55 mil still to be paid in December '23). This leaves 290 million to be paid out in the next 2 years – hence, current sell side projections are increase of dividend to 130 mil. for 2023 and 160 mil for 2024.

Similar dynamic was confirmed by the management. From the latest q3 ’23 earnings call: “…The real question, of course, with such results is what's happening with the dividend. So we still here show the old cumulative EUR 500 million payout promise, which means that, of course, the upcoming 2 years, there would be an increasing -- a meaningful increase in dividend every year.”

This is already quite attractive return, but it’s not the whole story. As the bank will probably earn around 500 mil eur only in ’23, even this increased dividend is much lower than the dividend payout ratio of 70% that was communicated in the IPO prospectus.

From the q3 ‘23 earnings call: “

“On the other hand, clearly, if you're delivering EUR 0.5 billion almost of profits, right? It is paying out 110 million and then a bit slightly growing the dividends, enough from the eyes of the investors. It's a legitimate and valid question…”

Accordingly, in almost every earning call in the past 6-7 quarters, investors are questioning, if and when, the bank plans to return to its 70% dividend payout ratio. So far, the management explanation has been that they are accumulating capital for one or more accretive M&A opportunities (in the amount of up to 4Bn eur RWA). This is not negative per se, because as you wrote in your write up, the two M&A deals they’ve done so far, have been incredibly successful.

But as no M&A deal has crystallised in the past 12 months, the management has been more open in discussing the capital allocation strategy going forward. In the latest earnings call they announced that the Board will be looking at all options and will communicate the outcome on the Investors Day, on 9th of May 2024.

From the q3 ’23 earnings call: “

“We have announced and now we can formally, of course, also confirm that as of December, we will officially kick off the strategising process within which we will really try to understand the revenue push for organic and/or M&A evolution in the upcoming midterm period…”

“So the news is good. We would not be paying less. We would eventually be paying more, but this, of course, depends on whether we will be able to find really meaningful value-accretive alternative deployments of capital. We hope that we have and we believe that this has been the case that in the last 3 to 5 years, we have gained your trust that we have been able to transact in terms of M&A. That we have been able to meaningfully not only acquire, but also integrate.”

“…So in case until end of April, mid of May, when we communicate a new strategy on the 9th of May, we didn't have anything meaningful on the horizon in terms of really concrete sizeable acquisitions, this might, I'd say, might well lead to a conclusion that we significantly -- to size up the dividend, right? We might think of share buybacks, but that's all hypothetical because this is all has to enter, of course, now the pipeline of discussions with our Board. The capital absorption is very high. The total capital adequacy is very high. The organic growth does not show such a potential to be able to consume this EUR 4-plus billion of risk-weighted assets, right?

So in this respect, if there is no really meaningful further acquisition potential in terms of really actionable assets in the upcoming, let's say, 12 months or 18 months, then this might rather mean we really revise the dividend payouts. But it's a bit too early. So we kindly ask you for a bit of patience, patience and trust.”

I personally think that M&A is still the most probable option (the bank has been trying to enter Croatian market for some time and this would be a very good outcome, but as you wrote, there are political hurdles, that might get resolved soon enough. Also, Albania has been mentioned as a potential market in the past, etc.).

But in case there is no meaningful opportunity, it is very positive that the management has started to communicate willingness to further significantly increase the dividend or even start buybacks.

Analyst question: "Given the share price valuation, is buyback something you consider on top of dividend must be better investment -- must be better investment than any M&A?"

Blaž Brodnjak:

This is definitely a valid alternative. We have so far not actually been actively working on it. But within the comprehensive assessment of deployment of capital… …this is not excluded. It is just that -- it is, of course, a bit more complex process requiring more tedious regulatory approvals and so on. But I would not, of course, eliminate it is an option, and it will be communicated in the package for the upcoming AGM. Archie, will you add anything?

Archibald Kremser

Nothing to add other than we hear from shareholders 2 different versions. One would like it, the other one would like it less because, obviously, the drawback is to take out liquidity from the stock. But we understand the question. I think more materially, we are focused on dividends as capital return. But yes, it's something we also try to understand better in whether there's a merit to it.

Hope this helps in giving bit more color on capital allocation options going forward. Thanks again for the great write up.

Beautiful write up, thank you. I'm from Slovenia and this is my biggest position by far.

Btw, coroporate tax in Slovenia is 19%, but it's possible it will increase to 22% in 2025.